Ramsey Castaneda, DMA

Navigation

Teaching Listen Research Online Education Photos LessonsEducation

USC, DMA, 2018CSULB, MM, 2014

UNT, BM, 2012

Contact

[email protected]

Ramsey Castaneda, DMA

Performance, Education, and Scholarship

- My Music Theory Resource Website

- Jazz Transcriptions

- TenTimesInARow.com

- Advice from Jazz Greats

- Thelonious Monk's Advice to Steve Lacy

- Elvin Jones' "Thoughts"

- Chick Corea's "Cheap but Good Advice"

- Discography-Transcription Collections (needs updating)

Teaching

-

2021 - Present

Crossroads School for Arts and Science

Chair, Upper School Music Department

-

2015 - 2022

Los Angeles College of Music

Courses taught: Advanced Theory and Aural Skills, Pedagogy, Big Band, Combos, Ensemble Workshops, Chamber Groups, and Private Lessons

-

2014 - 2018

University of Southern California

Courses taught: Private Jazz Lessons for Classical Saxophone DMA Candidates

Teaching Assistant:- Business and Legal Aspects of the Music Industry

- Introduction to the Music Industry

- Basics of the Music Industry

- Arranging for Popular Music Ensembles

- The Music of Black Americans

- Jazz History

-

2017 - 2018

Los Angeles Youth Jazz Ensemble

Co-director of Los Angeles based high-school jazz ensmble organized by USC Thornton School of Music's Music Teaching and Learning Outreach Program.

Listen: Selected Performances

On Michael Bublé's 2018 album, ❤, (pronounced, "Love").

A solo with Jon Hatamyia Group

A solo during the Paquito Rivera workshop at Carnegie Hall

A solo with Peter Erskine and the Disneyland All-American College Band

Saxophonist (all parts) on Disney's Making Today a Perfect Day for the TV show Best Friends Whenever

Saxophonist on Disney's

Sophia the First

Research

Online Education

As an undergraduate at the University of North Texas, I taught myself basic web-development to put online a Chris Potter discography that I had created. This first attempt at coding and publishing a web-project put me in contact with other jazz scholars and fans around the world and initiated meaningful musical connections that expanded my perspective of jazz beyond performance. During my doctoral studies, I took classes in interactive web and database development.

Over the past few years, I've enjoyed marrying my passions for music, theory, and history with code and pedagogy. Below are some of the projects I've created. I've created web-applications in PHP, SQL, Angular, Angular Universal, Vue, and of course JavaScript, HTML and CSS.

General Jazz History/Research

- A searchable and sortable Coltrane discography that includes publically available transcriptions

- A Google Street-View timeline of Coltrane's residences accompanied with biographical information and lists of recordings Coltrane made while living at particular locations.

- A searchable and sortable Chris Potter discography that includes publically available transcriptions

Database of Jazz Representation in Popular US Media

Currently under construction

jazzinpopculture.com

- A project to collect and catalogue representations of jazz in mainstream media. Particular attention is given to 1) the indexical significations of the word "jazz," particularly when spoken or referenced without accompaning audio or visual referents, and 2) the appropriation of John Coltrane as a symbol of "jazz."

- I have presented this research at JEN 2019 (Reno, Nevada) and Documenting Jazz 2019 (Dublin, Ireland). Continuing this theme, I am co-presenting related papers on photographic tropes in protoypical historic jazz photographs at JEN 2020 (New Orleans, IL) and Documenting Jazz 2020 (Birmingham, England).

Music Theory Flashcard Games and Interactive Articles

In mid-2018, I migrated all of my music theory web-applications to music-theory-practice.com, which now features approximatley 28 interactive music-theory articles, tutorials, and flashcards. A sample of those is below.

- Interactive flashcards featuring randomly generated questions in the form of "What is the X of Y," where X is a scale degree and Y is a key. For example, "What is the b13 of Ab," to which the user must respond with "Fb." Similarily, I also created Solfege Flashcards

- A tutorial on how to find the interval class vector of a collection of pitch classes. The calculator produces results in four formats: 1) a list of each interval pair, mod6, 2) standard ICV notation, i.e. < x x x x x x >, 3) a dynamically produced bar graph chart, and 4) notation of the collection on a treble clef staff.

- These flashcards draw from an array of transposing instruments and ask the user what written pitch would X instrument need to play to sound Y pitch. For example "What note would an Alto Saxophone need to play to produce this concert-pitch note?" Alternative, there is a set of flashcards for the opposite, what is the concert pitch note of Bb Clarinet's note, C.

Early Chris Potter Solos

Currently under construction

- Shortly after the online-publication of my Chris Potter discography in 2011, I became aquainted with a number of other Chris Potter afficanados and people close with him when he began playing professional as a young teenager. I have since aquired through these contacts a number of recordings featuing phenomenoual recordings of the young Potter. Analysis of a number of these solos was presented at JEN 2017 (Dallas, Tx), and the creation of a transcription book is in the works.

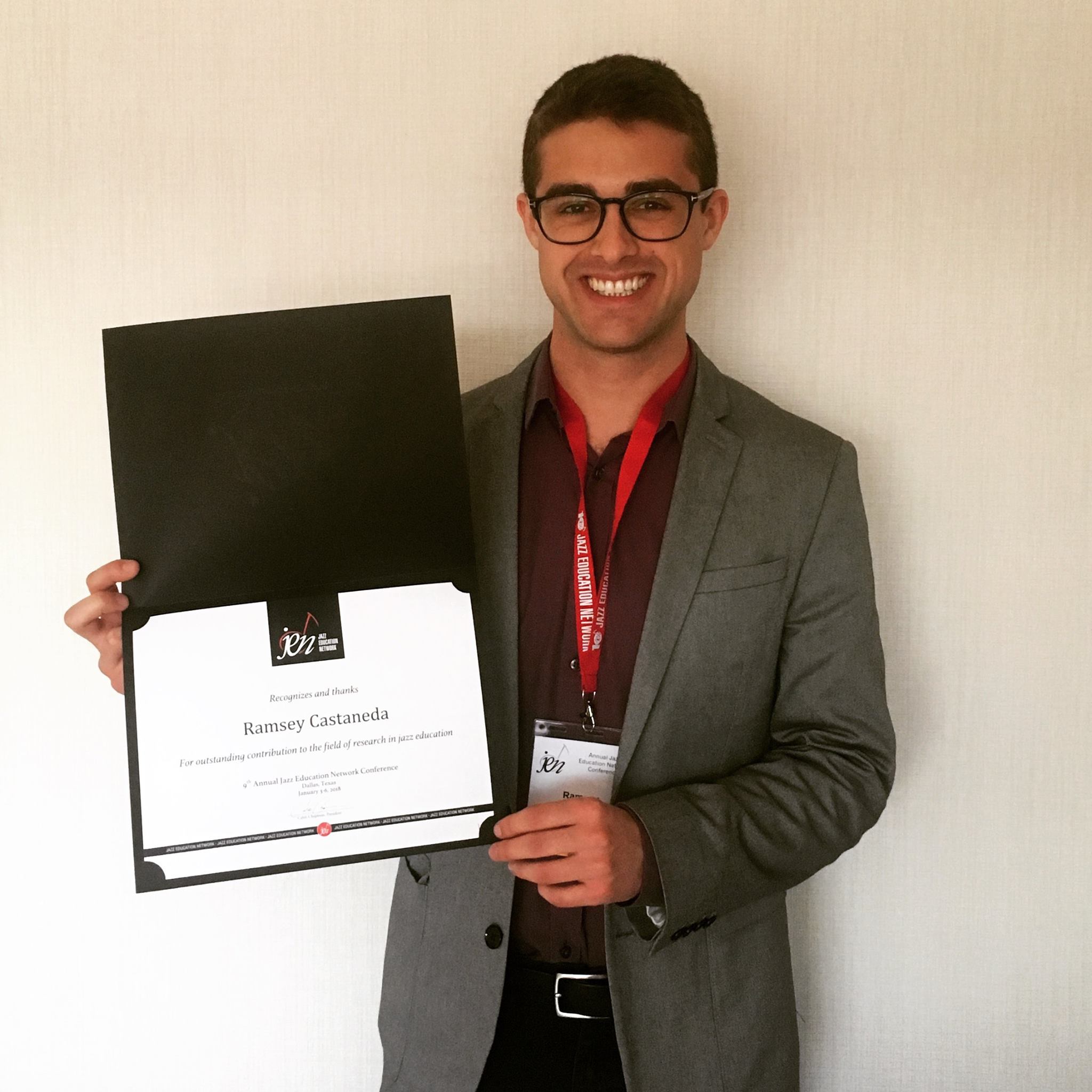

Photos

Lessons

I currently have openings for private lessons (saxophone, improvisation [any instrument], and music theory) in the Pasadena, CA area. I provide in-home lessons. Please contact me through email if interested.

I'm additionally available for masterclasses and workshops with high schools and colleges. Contact me through email if interested.